Several years ago, I took a Film 101 class at DeAnza College in Cupertino, California. I loved the class – I have not watched a movie the same way since. A key objective of the class was to learn about various aspects of representation in film. My final paper was a discussion of such aspects of two of my favorite films – Up in the Air and Lost in Translation. I’ve wanted to bring this analysis to my blog for years and have finally sat down to do just that. I really enjoyed diving into the many layers each film offers.

The principle idea in both Up in the Air and Lost in Translation is the complexity and value of relationships. LIT follows the relationship between Charlotte and Bob, a friendship developed while staying at the same hotel in Tokyo, which takes on a father-daughter connection but occasionally romance seems at their fingertips.

“The central relationship is explored from the contrasting perspectives of a woman in her early 20s and a middle-aged man each afflicted by different yet parallel doubts about the course their life respectively is taking or has taken.” – Rooney, from Variety[9]

Up in the Air, directed by Jason Reitman, follows Ryan, a man loyal only to an Airline.

“[I]t’s a movie about how one man living inside the cocoon of an overly detached culture comes to see the error of his own detachment. Up in the Air is light and dark, hilarious and tragic, romantic and real. It’s everything that Hollywood has forgotten how to do; we’re blessed that Jason Reitman has remembered.” Glelberman of Entertainment Weekly[5]

This post assumes, to some extent, that the reader has seen these movies; if not, you can find the synopses on IMDB. I have seen each film dozens of times; they are two of my favorites. The purpose here is not to walk through each movie end-to-end, but rather talk about how central themes are reinforced by sub-themes and motifs.

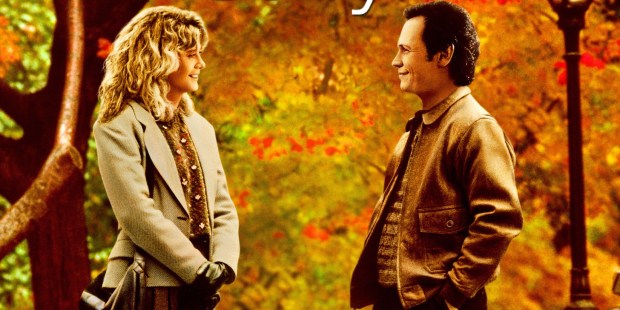

Lost in Translation

At the center of this film directed by Sofia Copola is a special but complex relationship between to travelers who meet in a Tokyo hotel. One is an older celebrity, Bob, in town to do a commercial for Japanese whiskey, the other is the tag-a-long spouse, Charlotte, a recent college graduate. Their immediate chemistry sparks a quick friendship and we follow them in their journeys through the week. At times there seems to be an affair on the horizon – like when they are out on the town. Other times Bob provides the support of a parent, like at the hospital and especially in the fantastic platonic scene of the hotel bed where Bob dispenses of life advice.

Ansen, of Newsweek Magazine, stated “Is it a paternal relationship or an erotic one? Is this a love story, or something just to the left of it? Part of what makes this movie so special is its delicate blurring of conventional boundaries.”[1]

This relationship is given a motif of the color orange – a color blurred with the red of love and the yellow of friendship. Orange can also represent safety – which these two undoubtedly feel in each other’s company. Rooney explains “[w]hile the relationship repeatedly appears poised to move to the next level, Coppola judiciously holds it back, introducing a degree of friction when Bob sleeps with a hotel lounge singer.”[9]

Adding texture to the main relationship exploration are other plays on relations. From Bob himself, to Charlotte’s husband’s former client to the lounge singer – there is another altitude from which these people operate. Yet with Bob, even while spending much of his time on camera, he doesn’t seem native to that world, there are “moments when he emerges from his shell of irony emotionally naked.”[1]

The relationship of our two protagonists and their environment is also a rich theme. The hotel – whether it’s the lobby, lounge, halls and room – is their safe hiding place from the world and where their relationship is grown from several initial run-ins. The city itself acts almost like a separate character, complete with glowing red heartbeats seen in the skyline vie from their rooms. A vibrant city begins as harsh and strange but evolves to being warm and familiar by the end.

“The director’s love and fascination for Japan are evident in every frame, from the neon-jungle aspect of Tokyo’s congested streets to the occasional departures into the calm of its gardens and temples.” – Rooney[9]

Captured incredibly well is the overwhelming fog of international travel, and the confusion it can create for us. Trouble sleeping, being more active at night than during the day, feeling a bit lost. Very quiet scenes help to convey the isolation and loneliness that can emerge. Many shots of our characters show have them slightly out of frame or disproportionate to the surroundings. We see Charlotte paused to decipher a complex subway map. Bob is found struggling with communication through translators and his own wife.

To put the final touch on all of this, the director brings the relationship of the movie and the audience to the top – we are left with a final scene which is both satisfying and frustrating all at once.

“When it comes time for Bob to leave Tokyo, the awkwardness of the goodbye is heightened by the weight of certain unexpressed feelings, but this is satisfyingly resolved in a tender final exchange in which Bob’s words to Charlotte remain unheard.” – Rooney[9]

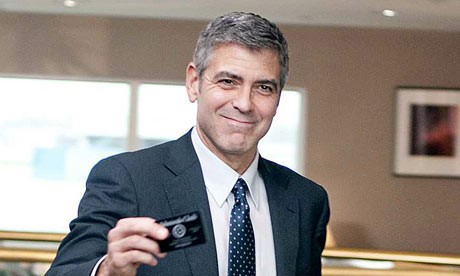

Up in the Air

Up in the Air follows the life of an always-on-the-road consultant who helps companies manage layoffs. His occupation, where he in effect is pretending to be part of the client company, sets the tone and will be only one of several false or shallow relationships. This focus highlights an interesting relationship that we can all relate to – that of ourselves with our employers. An interesting and very effective choice in direction here was the decision to use real people/non-actors who had recently lost their jobs. The director noted being surprised about their reality after talking with them, as Norris from NPR discussed with the director:

“REITMAN: You know, if you would’ve asked me before I did this movie what is the worst part about losing a job in this type of economy, I would’ve probably said the loss of income. But as I talked to these people, that actually rarely came up. What people said time and time again was, I don’t know what I’m supposed to do. And this was kind of a startling statement, that it was really about a lack of purpose. They would say, you know, after I finish this interview, I’m going to go get in my car and I have nowhere to be. And I can’t imagine thinking that every day.”[8]

Besides being a consultant, Ryan is a motivational speaker. But keeping in harmony with false relationships, his message is hardly motivational – it’s about abandoning attachment to things and people. He practices this himself. Ryan has extended family, but he’s been distant from them. This is represented by a cardboard cutout of his soon to be married sister and her fiancé, which he is to take photos of on his travels. He handles the cardboard family with more care than the actual humans.

Ryan is loyal, however, to his favorite airline. He’s earned a rare number of miles with his work and is saving them to reach a milestone – ten million miles. Brands and loyalty in general are important to him, shown in his quick dialog with Alex on the topic one night in the hotel lounge. Director Reitman on Ryan’s desire to collect miles, when speaking with Jian Chomeshi, asked “why do we collect anything? Instead of filling our life with meaningful things, we often have collections of who knows what – it’s as if we are trying to confuse ourselves into believing that our lives are complete, when in fact they’re not.”[4]

Ryan has two new relationships to navigate in the film. First, a new younger employee, Natalie, has arrived on the scene with big ideas to modernize the company with remote technology so that people don’t have to travel to help with the layoffs (saving the company money and restoring work-life balance for most employees). Since this prospect threatens Ryan’s world, he pushes back and the two are sent on the road together so Ryan can show Natalie the ropes. What begins as a rather contentious partnership evolves to an appreciation liken to the parental relationship between Bob and Charlotte in Lost in Translation. This may be the only authentic relationship in the entire movie, but we don’t learn that until near the end.

On the road Ryan has met another corporate road warrior in Alex. They hit it off and are soon swapping schedules and changing flights to be in the same city whenever possible. Ryan finds himself falling for Alex. There is a motif with use of the color red when the story is focused on this relationship. One day he tries to surprise her at home, only to face the same unwelcome surprise that he lays on his client’s employees – what he thought he had is gone. She’s living a second life with a family and admonishes him for visiting her since, from her point of view, it was clear from the beginning that this was just a fun fling on the road.

This film also depicts the relationship of ones environment. With airports and hotels making Ryan feel at home, he’s comforted by a sparsely decorated home base. “His modest apartment in Omaha resembles an undecorated motel room,” wrote McCarthy of Variety Magazine.[7] His pockets full of hotel keys, the satellite view images of cities and use of maps are all supporting motifs. When Ryan sees the U.S. map come to life with photos and people at his sister’s wedding, he’s especially struck. For this aspect, there is a motif of the color blue which stands for Ryan’s relationship with the sky and finding comfort there. Ryan even makes several references to space in the movie, leading us to believe he would be even more isolated from mankind if possible.

Along with the airports is the travel process itself. From his efficient and mechanical rapid-packing to his backpack speech in his motivational gigs – and don’t forget the exchange between Ryan and Natalie about her luggage at check-in. “Ryan is a pure product of the new America, an addict for a life in which everything is systemized,” wrote Dargis of the New York Times.[3]

We start with Ryan, who is all about “Elevated detachment”[3]. Dargis said “In Up in the Air, Clooney gives his most fully felt performance to date as a smooth hedonist who comes to realize that he may be drowning.”[3] But at the end, we find Clooney has changed. Where at one point in the movie we think it’s Alex that would change him, we see in the end it was Natalie. He reaches his miles goal, but it’s lost its charm; he’s seen taking Natalie’s advice and picking a destination, he gifts miles to his sister and her new husband, and made sure Natalie landed well.

Summary

Through the use of key relationship themes, subthemes and motifs, Up in the Air and Lost in Translation share a point of view on the importance for people to have meaningful relationships, no matter how they arise or how long they endure. On Lost in Translation, Ansen said “Their connection is what this small, unforgettable movie is about: a transient, magical, restorative meeting of souls”[1]. Biancolli of SF Gate wrote, “Reitman the screenwriter gives Reitman the director an excuse to ponder the spaces between us and the ties that bind. Or don’t.”[2] These two films are excellent examples of direction which show the importance of thoughtfully layering in sub-themes and motifs that strengthen the underlying message.

Sources

[1] Ansen, David. (September 14, 2003). Scarlett Fever. Newsweek Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.newsweek.com/scarlett-fever-136731

[2] Biancolli, Amy. (December 4, 2009). Review: ‘Up in the Air’. SF Gate Movie Review. Retrieved from https://www.sfgate.com/movies/article/Review-Up-in-the-Air-3208465.php

[3] Dargis, M. (December 4, 2009). George Clooney and Vera Farmiga as High Fliers. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/04/movies/04upinair.html

[4] Ghomeshi, J. and Reitman, J. (September 22, 2009). ‘Up in the Air’ Director Jason Reitman on Q TV. Q on CBC. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VwAf3o-EcQw

[5] Glelberman, O. (December 20, 2009). Up in the Air. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved from: http://www.ew.com/article/2009/12/30/air

[6] Lost in Translation. Dir. Sofia Coppola. Per. Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson. Focus Features, 2003. Film.

[7] McCarthy, Todd. (September 6, 2009). Review – Lost in Translation. Variety Magazine. https://variety.com/2009/film/markets-festivals/up-in-the-air-2-1200476402/

[8] Norris, M. (November 20, 2009). Director Jason Reitman Finds His Feet ‘Up in the Air’. NPR. Retrieved from: http://www.npr.org/templates/transcript/transcript.php?storyId=120951819

[9] Rooney, D. (August 31, 2003). Lost in Translation. Variety. https://variety.com/2003/film/awards/lost-in-translation-6-1200539681/

[10] Up in the Air. Dir. Jason Reitman. Per. George Clooney, Vera Farmiga and Anna Kendrick. Paramount Pictures, 2009. Film.